04 Mar 2024: Doing What You Love: A Christian Critique of Work, Passion, and Contentment

A Christian Critique of Work, Passion, and Contentment

Dr. Mark Wm Cawman

Associate Professor

Azusa Pacific University | School of Business and Management

and

Dr. Todd Pheifer

Associate Professor

Azusa Pacific University | School of Business and Management

ABSTRACT

The popular mantra or philosophy of “do what makes you happy” in life and vocation, is partially backed by research. Job satisfaction is significantly positively correlated to job engagement and job performance. However, there are tensions with the Christian perspective of contentment, and “what makes you happy” is both dynamic and dependent on more than the circumstances of employment. This article considers both the secular and Christian literature as well as the biblical narrative, and elucidates tensions, challenges, and requisite considerations in balancing the concepts of work, passion, and contentment. Even outside of the Christian focus, individuals may wrestle with balancing loyalty and contentment with the motivation and desire for change. The research supports that meaningfulness, purpose, and an others-centric motivation can bring more satisfaction and happiness than self-centered stimuli. This article contributes a unique perspective to the study of vocation, both to the Christian and secular audience.

Keywords: passion, satisfaction, purpose, contentment

Introduction

A significant step in career or vocational considerations is introduced in this article as the construct of passion. What gets an individual talking with enthusiasm about what they enjoy doing the most, or what makes them excited to start their day? What fosters perseverance and sustains people to pursue goals and outcomes that may take years to complete? Literature supports that job satisfaction correlates with engagement, which then supports job performance (Abdel-Halim, 1980; Cherrington & Lynn England, 1980; Iaffaldano & Muchinsky, 1985; Judge et al., 2001; Judge et al., 2012; Porter, 1969; Roznowski & Hulin, 1992). Roznowski and Hulin suggest that this literature is very comprehensive: “Job satisfaction…has been around in scientific psychology for so long that it gets treated by some researchers as a comfortable ‘old shoe,’ one that is unfashionable and unworthy of continued research…” (Roznowski & Hulin, 1992). That said, the downward trend in tenure and the “great resignation” of the 2020 decade has focused significant research on satisfaction, work culture, and the employee’s sense of meaning toward increasing retention and reducing turnover (Hirsch, 2021; Sheather & Slattery, 2021). While some organizations may grasp the concepts and value of satisfaction and engagement, loyalty is a quantity that can be lacking on both sides of the work relationship. This puts pressure on both individuals and organizations to examine how passion can be cultivated, both immediately and in a sustained way, particularly when routinely changing jobs is increasingly acceptable and a norm in today’s society.

Amidst this reality, there is a significant modern mantra of “do what you love and what brings you joy” that deserves consideration relative to God’s design and the Christian individual’s vocational choices. If an individual fails to consider an alignment of employment and passion or continues in enervating tasks with a lack of stimuli — ennui (tedium, boredom, fatigue, enervation, lassitude, monotony) is often the result. This can cause many issues in both personal and work outcomes (Gosline, 2007; Smith, 1981; Vodanovich, 2003). In some cases, individuals disassociate or disengage through existential ennui arising from self-alienation or doubts about purpose in life or value (Kim et al., 2018). Satisfaction is not all about money or compensation. While employment is necessary for livelihood, there are many factors beyond monetary compensation to consider in overall satisfaction (Locke, 1976, pp. 1301–1302). This suggests introspection and considerations for the Christ follower. Should people pursue a mindset of personal satisfaction or contentment in their work, or should their attitude be more focused on obedience to a spiritual calling? Put another way, should obedience to calling be the element that fosters contentment, rather than looking for satisfaction in the job itself?

Often this is not an all-or-nothing answer, but if a significant percentage of the time and tasks involved in a job, career, or vocation serve to engage the individual – they have passion, engagement, and job satisfaction. The Pareto Principle originally credited to Dr. Joseph Juran [ circa 1937] suggests that 80% of outcomes are attributable to 20% of the causes (Juran & Godfrey, 1999). Koch and Brealey suggest that 20% (inputs) result in 80% outputs, 20% of causes result in 80% of consequences, and 20% of effort can yield 80% of results (Koch & Brealey, 1997). By a very loose extension, one could posit that if 20% of the time (e.g., one day out of five, or eight hours out of a forty-hour week) an individual was engaged in satisfying activities, they would be 80% satisfied with their job, career, or vocation. Sometimes individuals have a very low percentage of time and tasks involved in a job, career, or vocation that really serve to engage them, which applying the Pareto Principle could actually amount to far less than 20%. If only a few attributes or components of a vocation, job, or career; serve to engage the individual, those attributes deserve a critical look to see if different employment or vocational alignment might serve a larger portion of these satisfying attributes. Everyone can have a bad day or even a tough stretch, but the consideration of passion in a career or vocation is to critically consider if the individual is engaged and satisfied with the larger portion of the time and efforts vested. This is important to assure that they stay the course while being productive, fulfilled, and experiencing a sense of purpose.

Changing Versus Lifelong Passions

Judeo-Christian teachings suggest that in conversion (salvation) and repentance, the Christian leaves the old life and previous “passions” that were rooted in sin and darkness. “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, this person is a new creation; the old things passed away; behold, new things have come.” (2 Corinthians 5:17). Desires and passions are not inherently evil but can be good or bad depending on whether they are God-centered or self-centered (Tarrants, 2020). A converted or new set of passions can be both immediate and progressive. In conversion, individuals want to please God and their focus and interests change. Ideally, that conversion continues as they grow in maturity and discernment, and as individuals continue looking for ways to serve God’s kingdom.

God calls those who receive His grace to love Him supremely and enthrone Him as their heart’s desire (Deut. 6:4). As they seek to do so, a paradoxical change occurs. The initial thirst of their hearts is satisfied by His grace and love. But in time, this very satisfaction fuels thirst for deeper intimacy and communion with Him (Tarrants, 2020).

The Bible is rich with examples of desires and passion for God, experienced by the believer, and grown or strengthened when the Christian walked closely with God in intentional communion and attendance to the “means of grace.” Conversely, Christians are instructed not to love the things of this world and to submit to desires of the flesh – thus suggesting some human desires and Christian passions are in tension. Many human desires need to be kept in check for obedience and loyalty to grow into a sustained mindset. God demands that He be put in first place in the hearts and lives of believers, and Christians become excited and passionate about Godly things and sharing the Gospel. This does not mean that all vocations must be spiritual or religious, nor that vocations cannot serve secular passions or functions. What it does mean, is that there should be a check and balance in the Christian life, to assure that the pursuit of passions in vocation is congruous with the Christian identity, and is subject to the will of God.

Christians may struggle to truly leave their old life behind or to know how to fully live into God’s will or a Christian identity. In some cases, individuals may not fully differentiate between a faith-infused vocational mindset, a more worldly and secular mindset, or a career and overall engagement that evolved without any real intention. Some individuals are known for an intentional and missional approach to work and career. Others serve in less missional roles but are loyal and faithful because they feel a sense of calling to a particular field.

Some individuals are known for their lifelong passion(s). For example, some people love trains when they are a child and continue to be a train enthusiast and hobbyist as an adult. Other non-vocational passions can include sports, personal projects, developed skills, and various micro-communities, engagements, or commitments that take up measurable time in an individual’s schedules. There is nothing wrong with a lifelong or hobbyist passion, and when these can be lived into a vocation, it can be very satisfying for the individual. There is a saying that “if you do what you love, you will never work another day in your life” (Unknown). Most individuals experience one or more lifelong or hobbyist passions that are partof their identity. The Christ follower must ask whether their passions are aligned with Biblical teachings, if they are primarily focused on worldly gain, or if they prioritize energy and time appropriately. People must also ask themselves whether their habits, lifestyles, and passions have become so familiar, they are difficult to differentiate from their worldview.

Other passions shift with different stages of the human life cycle. Maybe there are childhood passions that do not persist, and eventually, even mid-life passions may give way to new satisfying stimuli at an older age and/or late in life. Sometimes these shifts are necessary and healthy, as some earlier life passions such as high-intensity sports are less possible as the human body ages. “When I was a child, I used to speak like a child, think like a child, reason like a child; when I became a man, I did away with childish things” (1 Corinthians 13:11). As people age, it can be harder to let go ofother habits and interests, simply because they have been part of life for so long.

The consideration of passion in the context of vocation is a dynamic process as shown in Figure 1 (the “The Dynamic Considerations of Passion” model) related to the life-cycle period and/or Christian conversion and maturity. It is important to consider if the desire for a vocational change is for a current and transient passion, or if it might serve in some permanent satisfaction. Will satisfaction, joy, and engagement expire in a later lifecycle stage, and is the passion Christ or world-centered? While this is a necessary consideration and process, it is not necessarily a binary decision. It is possible that an individual should or could pursue a vocation with a known expiry or for a period of time. Sometimes a vocation or a specific task is not intended to be a life-long engagement. It may temporarily serve a specific need, fulfill a duty or service, provide a platform for Christian influence, or monetarily advantage and prepare an individual for “something next.” An example of a temporary vocational engagement is military service. Individuals serve for a period and for a service, but may not consider a military career. There may or may not be defined beginning and end points to these temporary assignments. The military example is a good one in terms of a measurable, fixed period, but other vocational lines are more blurred. Regardless, individual should consider the dynamics of changing passions and make informed decisions rather than blindly following the desires of the here and now.

Figure 1: The Dynamic Considerations of Passion Model

Note: Developed by the Author as a Conceptual Model

A tension with this model is that stages of faith and life-cycle do not necessarily or always correspond to the stages of career. Growth in many areas of life is not always linear, particularly in the faith journey or in the pursuit of certain vocational pathways. What may be seen as a setback in a vocational journey may actually be a God-directed event that must be processed through the lens of ever-growing faith or a period transitional opportunity. Christians must continually look for how God is using a current situation for His glory (Isaiah 26:8).

The Relationship between Passion and Purpose

Christians (among others) may struggle with the ideas of contentment and passion as themes that are in tension – possibly even considering contentment as the correct, more biblical, or Christian answer. The Apostle Paul asserted that “…Godliness actually is a means of great gain when accompanied by contentment” (1 Timothy 6:6). The author of Hebrews further says that “Make sure that your character is free from the love of money, being content with what you have; for He Himself has said, “I will never desert you, nor will I ever abandon you” (Hebrews 13:5), suggesting that the only true satisfaction comes from an eternal relationship with Jesus.

As individuals have sought to pay the bills, they may have ended up in a role that they would not necessarily choose and that does not provide any joy, as noted in Ecclesiastes 6:2. They start “dreaming about something different — different, more comfortable pay; different, more empowering boss; different, more fulfilling responsibilities” (Segal, 2017). Segal suggests that a modern and secular culture pushes the idea of following the heart and doing what one loves, but that there are some realities that may not exist or pay the bills. Ephesians 6:5-8 refers to bondservants and suggests that in serving as unto the Lord, he/she will receive back from the Lord. Christians can glorify God in the job they have and God can give them joy, passion, and contentment. Segal (2017) says “bring those dreams to your day job, instead of looking for happiness in your dream job.” The secular viewpoint (more so in capitalistic and individualist societies) is to follow the dream and do what satisfies the individual – making a change if there is little or no satisfaction. This viewpoint is all about the individual versus a perspective of the Christian worldview. Instead, the story should be about God and serving others. If this is the narrative, there can be contentment and satisfaction. This suggests that often, there is a distinct relationship that exists between purpose and passion. Sometimes, a change is warranted, but less so from the perspective of transient pleasure, and more to align with that which “gives essence to what we do and brings fulfillment to our lives” (Chalofsky, 2003, p. 74). Meaningful work that gives joy and passion often occurs when an individual perceives that there is a connection that is authentic between their work and a life purpose beyond themselves (Bailey & Madden, 2016). Therefore, the person who is not content in the worldly aspects of their vocation may still achieve spiritual contentment through prayer and surrender (Galatians 5:24, John 4:34).

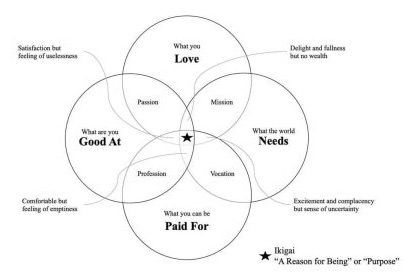

There is a concept that puts purpose and passion together in a model. Andrés Zuzunaga created a Purpose Venn Diagram, often misattributed by Western scholars to the Japanese concept of Ikigai and noted or often mistakenly cited as the Ikigai Venn Diagram shown below. This should be credited to Andrés Zuzunaga and known as the Zuzunaga Purpose Venn Diagram (Kemp, 2020). It does not originate from a Christian perspective, but it is very adaptable to many faith-based vocational considerations and is worth considering under the principles of purpose and passion. Often individuals who lack passion or satisfaction relate this to lacking meaning or purpose, and thus these constructs are very intertwined.

Figure 2: Zuzunaga Purpose Venn Diagram

Note: Adapted from a depiction of the Andrés Zuzunaga Venn Diagram (Impactivated, 2019), misidentified as the Ikigai Venn Diagram (Kemp, 2020).

A faith-integration perspective on this diagram may include an adaptation of the section called “What you are Good At.” Instead, the mindset may be, “What gifts has God equipped you with to serve His kingdom?” This may be paired with an adaptation of “What the world Needs,” which can synchronize with a faith perspective as long as that “Need” is considered within the context of what “God has prepared” (I Corinthians 2:9). Or, the phrase may be adapted to read something like, “What is God’s plan to use me?” As noted above, it is acceptable to consider elements of God-provided compensation (“What you can be Paid for”). Also, by God’s grace, there are many individuals who are granted opportunities to pursue passions that fit into the general category of “What you Love.”

Individuals who do not currently “love” a job should not necessarily look for other options as a default reaction. A period of personal dissatisfaction may simply be an opportunity for growth, or waiting. Through a more deliberate process, engaging something like this diagram, the individual can consider priorities, majority focus, and God’s will – through introspection and discernment. A more purposeful process of discernment, introspection, and alignment to God’s will can suggest change or persistence. Regardless of the outcome, a contentment with the decision is improved over individuals who just react or “follow their pasion.”

Summary

The secular individual-centric focus on passion (e.g., “do what you love and what makes you happy”) is sometimes not aligned with the Christian worldview, and there is a lot to be said for contentment. That said, when the focus is on serving God and others, and the mission offers a broader transcendent life purpose that goes beyond selfish desires, real satisfaction can occur in holistic meaningfulness. Ignoring the idea of passion (suggesting yielding to contentment only) does not provide intrinsic motivation or yield sustainable results. There is thus interactivity between passion and purpose that roots passion in the sense of meaningfulness. It is also important to remember that passion can push engagement and zeal and these realize improved productivity and outcomes in life. Passions can be lifelong, seasonal, or transient so some discernment is required to consider tenured engagement in vocational alignment. Passions can also be of the world and self, or be “converted” in the Christian, and can also be nurtured and matured over time. Passion as a construct can be an elusive quantity and quality, but when it is applied to the faith journey and vocation, it can be the fuel that unlocks an amazing synchronicity with obedience to God’s calling.

References

Abdel-Halim, A. A. (1980). Effects of higher order need strength on the job performance — job satisfaction relationship. Personnel Psychology, 33(2), 335–347.

Bailey, C., & Madden, A. (2016). Time reclaimed: Temporality and the experience of meaningful work. Work, Employment and Society, 31(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017015604100

Chalofsky, N. (2003). An emerging construct for meaningful work. Human Resource Development International, 6(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/1367886022000016785

Cherrington, D. J., & Lynn England, J. (1980). The desire for an enriched job as a moderator of the enrichment—satisfaction relationship. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 25(1), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(80)90030-6

Gosline, A. (2007). BORED? Scientific American Mind, 18(6), 20–27.

Hirsch, P. (2021). The great discontent. Journal of Business Strategy, 42(6), 439–442. https://doi.org/10.1108/jbs-08-2021-0141

Iaffaldano, M. T., & Muchinsky, P. M. (1985). Job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 97, 251–273.

Impactivated. (2019, May 19). https://impactivated.com/2019/05/19/impact-and-life-purpose-with-ikigai/

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Theresen, C. J., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376–407. https://doi.org/10.1037///0033-2909.127.3.376

Judge, T. A., Hulin, C. L., & Dalal, R. S. (2012). Job satisfaction and job affect. In S. W. Kozlowski (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (pp. 496–525). Oxford University Press.

Juran, J. M., & Godfrey, A. B. (1999). Juran’s Quality Handbook (5th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Kemp, N. (2020, February 4). Ikigai Is Not a Venn Diagram. Ikigai Is Not a Venn Diagram. https://ikigaitribe.medium.com/ikigai-is-not-a-venn-diagram-cca7abba323

Kim, J., Christy, A. G., Schlegel, R. J., Donnellan, M. B., & Hicks, J. A. (2018). Existential ennui: Examining the reciprocal relationship between self-alienation and academic amotivation. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(7), 853–862. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617727587

Koch, R., & Brealey, N. (1997). The 80/20 principle: The secret of achieving more with less. Long Range Planning, 30(6), 956. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0024-6301(97)80978-8

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology(pp. 1297–1349). Rand McNally.

Porter, L. W. (1969). Effects of task factors on job attitudes and behavior (A symposium). Personnel Psychology, 22(4), 415–418.

Roznowski, M., & Hulin, C. (1992). The scientific merit of valid measures of general constructs with special reference to job satisfaction and job withdrawal. In C. J. Cranny, P. C. Smith, & E. F. Stone (Eds.), Job Satisfaction (pp. 123–163). Lexington Books.

Segal, M. (2017, March 15). The secret to job satisfaction. Desiring God. https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/the-secret-to-job-satisfaction

Sheather, J., & Slattery, D. (2021). The great resignation—how do we support and retain staff already stretched to their limit? BMJ, n2533. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2533

Smith, R. P. (1981). Boredom: A review. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 23(3), 329–340.

Tarrants, T. A., III. (2020). The transformation of our heart’s desires. Knowing & Doing, Spring. Https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/The_Transformation_of_our_Hearts_Desires

Vodanovich, S. J. (2003). Psychometric measures of boredom: A review of the literature. The Journal of Psychology, 137(6), 569–595.