02 Mar 2025: Pastors are People Too: How Self-Perceptions of Humility, Shame, and Spiritual Well-being are Experienced by Evangelical Megachurch Pastoral Leaders in Southern California

Pastors are People Too: How Self-Perceptions of Humility, Shame, and Spiritual Well-being are

Experienced by Evangelical Megachurch Pastoral Leaders in Southern California

Jason A. Miller, PhD

Adjunct Professor, Talbot School of Theology & Biola University

Research Associate, TEND (tendwell.org)

Abstract

When it comes to pastoral leaders, Christian culture has often expected them to be beneath pride and above shame, serving as the anchor of spiritual well-being for the congregant; without giving much consideration to the pastor’s own self-perceptions and experiences of humility, shame, and spiritual well-being. This article explores how 149 pastoral leaders in mega-churches in Southern California perceive of these variables in their life, the relationship these variables share, and differences found in gender, years a Christian, years in ministry, and pastoral role. Suggestions are made for both educator and pastoral leader to consider in light of the findings.

Keywords: humility, shame, spiritual well-being, pastor, leader, megachurch

The Context

In 2016 Jimmy Dodd called the Church to something it has long known and struggled to achieve: the need to no longer layer expectations on pastors to somehow be above the human experience. The impetus then for the research covered in this article was to test and consider the phrase, “Pastors are humans too.” The research was conducted in 2019, right before the pandemic caused this researcher to set the project aside and explore the impact that Covid-19 was having on the landscape of pastoral ministry (Miller and Glanz, 2021; Miller and Lemke, 2022).

Research on pastoral leaders and their internal motivators has in the past proven difficult, in part because pastors have historically believed that protecting their image is vital to their professional capacity. [1] When one considers this propensity towards pastoral silence along with what appears to be an increase in the reporting of sexual abuse and spiritual abuse scandals (Bailey, 2018), infidelity, [2] suicide rates (Blair, 2018) and burnout amongst clergy [3] it would appear that pastors may be internally suffering in ways they either are unaware of or perceive they have limited safe places to share. The goal of this research, then, was first to explore the perceptions of humility, shame, and spiritual well-being pastoral leaders held about themselves and compare this with the self-perception of the general populace; second, to observe how these three variables interact with each other; third, how these variables affect different demographics within pastoral ministry; and fourth, to consider what we as pastors and educators can learn about ourselves and our students to help the Church further shape healthy Kingdom living.

The Details [4]

One hundred and forty-nine (149) pastoral leaders at twenty-three (23) Southern California Evangelical mega-churches participated in a survey that included five (5) psychometrically tested scales exploring their perceptions of humility, shame, and spiritual well-being, both personally and professionally. These variable were not directly mentioned in the survey as they have been shown to be “loaded terms,” words that can evoke a changed response when the term is used. The study was executed with an expectation of further “humanizing” the pastoral role, hypothesizing that humility and unresolved shame would be evident in pastoral leaders, competing with each other, having specific relationships with spiritual well-being, and that specific demographic groups – including gender, role, years identified as a Christian, years in ministry, and years in current position – might prove to have differences when these variables are considered.

The Definitions

Pastoral leaders were defined as full-time staff within the church who, as part of their role, are expected to see to the spiritual care of others. Mega-church refers to churches with 2,000+ weekly attendance. Evangelical was identified as either a signatory of the National Association of Evangelicals, or holding articles of faith that align with the NAE statements of faith. Humility was defined by three aspects identified in Positive Psychology literature: an accurate view of self (Tangney, 2000) and a lowered defensiveness (Hill, Laney, Edwards, Wang, Orme, Chan, & Wang, 2017) leading to an other’s-oriented posture (Hook, Davis, Owen, Worthington Jr., & Utsey, 2013). Shame was defined from psychological literature as an unresolved and internalized self-perception that the individual is at their core irreparably broken, flawed, inappropriately missing something, incomplete (Lewis, 1971; Tangney & Dearing 2002). Spiritual well-being (SWB) involved a sense of God’s presence within both personal and professional settings (Proeschold-Bell, Yang, Toth, Rivers, & Carder, 2014).

The Findings

It turns out, where shame and SWB are involved, pastors are indeed people too. While marginally lower, their perception of shame is similar to that of the levels noted in a variety of studies of individuals who are not pastors. This was especially true both for shame and SWB when considering roles at the director or associate pastoral level. [5] With humility, the comparison is a bit more difficult, as there appears to be a ceiling affect, by which the average humility score skewed high. [6] More research is needed to better understand to what extent pastoral leaders are able to discuss humility as they experience it, and to what extent they report on humility in light of the expectation of their role, but even with this smaller range of scores, significant relationships among the variables were detected. Two intriguing patterns were observed regarding the perceptions of these three variables. Humility and SWB rise and fall together – when one is moving so is the other. Humility and shame also move together, however they move in opposite directions, such that when perceptions of shame are rising perceptions of humility are dropping and vice versa. Interestingly, SWB and shame showed no significant relationship, though it’s relationship with humility suggests a negative relationship with shame and invites further exploration. When considering gender, role, and age demographics, a variety of notable distinctions were identified:

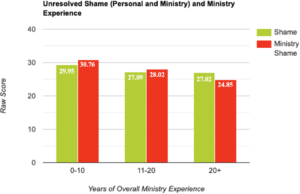

1. Years of Overall Ministry. Pastoral leaders appear to be more likely to experience higher levels of unresolved shame in the earlier years of their vocational ministry, with their perception of unresolved shame appearing to drop over time.

Fig. 1 Unresolved Shame (Ministry and Personal) and Overall Ministry Experience

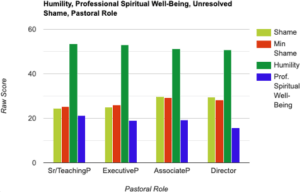

2. Pastoral Role. Pastoral leaders in higher roles are more likely to perceive themselves as more humble than those leaders who serve in lower roles of authority. Pastoral leaders in lower levels of role are more likely to perceive of themselves as feeling more shame, than those leaders who serve in higher roles of authority. Pastoral leaders who hold higher levels of role and authority also hold higher levels of spiritual well-being.

Fig. 2 Humility, Professional Spiritual Well-Being, Unresolved Shame, and Pastoral Role

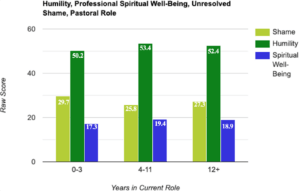

3. Years in Current Role. Pastoral leaders who are new to their role are less likely to perceive of themselves as humble than those who have held their role for 4–11 years. Pastoral leaders new to their role are more likely to perceive of themselves shamefully than those who have been leading 4–11 years.

Fig. 3 Unresolved Shame, Humility, Spiritual Well-Being and Years in Current Role

4. Years a Christian. Pastoral leaders who were Christians for 20–30 years were more likely to perceive of themselves personally shamefully than those who had been Christians for 30+ years. However, pastoral leaders who have been Christians for 30+ years see an increase in experiencing shame professionally. Pastoral leaders who are in the beginning stages of their Christian faith (0–20 years) are more likely to rate their perception of spiritual well-being at significantly higher levels than those who are at the middle stages of their faith journey (20–30 years).

Fig. 4 Unresolved Shame, Spiritual Well-being, and Years a Christian

5. Gender. Women were more likely than men to perceive of themselves with a higher sense of humility, and a higher sense of personal spiritual well-being. However, when looking at professional vocational ministry, female leaders held a lower sense of spiritual well-being then their male peers.

Fig. 5 Professional Spiritual Well-being, Humility, and Gender

The Practical Implications: So What?

So, what do we make of this? How might these findings inform our work as pastoral leaders and educators and how might we use it? At the meta level, the overarching theme that cannot be overstated is how pervasive unresolved shame is, the concept that “I am irreparably broken.” Shame has been shown to drive both passive activities such as depression and paralysis and fuel active movements of striving and pride (Kim, Thibodeau & Joregensen, 2011; Kellert, Mollen & Rosen, 2015; Gibson, 2016; Schaumburg & Flynn, 2012. Crosskey, Curry & Leary, 2015). One should consider the impact of this in our daily leadership experiences. An unresolved shame narrative may deeply affect a variety of domains in pastoral leadership, such as who we hire and fire, what we preach and teach on, how we use our institutional resources, and what we turn to make meaning for ourselves, to name a few.

Yet this study suggests humility—an accurate view of self–stands as the natural antidote. Though we have all been given a new identity in Christ, it seems we still struggle with pre-cross muscle memory and fear. We would do well to imitate the lived experience of Jesus who, though he had not begun his ministry activities yet, at his baptism heard the Father say, “this is my son in whom I am well pleased” (Matthew 3:17). This accurate view of self, this declaration of identity, appears to have fueled Jesus’ ministry, lowering his defensiveness such that he was able to serve unto his death through a healthy others-oriented lens. How might anchoring ourselves and our students in the identity statements that God speaks over us combat the fatigue, temptation, and imposter syndrome we experience and observe in both the classroom and the pulpit? If we were to proclaim over ourselves and each other that which God says we are – Heir (Galatians 3:29, Titus 3:7), Child (Romans 8:16; 1 John 1:12, 3:1), Friend (John 15:13-15), Citizen (Phil 3:20; Eph 2:19), Saint (Romans 1:7, Jude 1:3; Eph 5:3), Servant (John 15:20; Acts 26:16), Steward (1Peter 4:10; 1 Cor 4:1–2, 9:17), Soldier (2 Tim 2:3; Eph 6:11–17), Priest (1 Pt 2:5; Gal 3:28), Member of the body (Romans 12: 3–8; Ephesians 4:4), Indwelt (1 Cor. 3:16, 2 Tim 1:14), Gifted (1 Cor. 12:7–11, 1 Pt 4:10), Called (2 Tim 1:9; Gal 5:13; Eph. 1:18, 4:4), Invited (Matt 11:28, Rev 3:20), Powerful (Acts 1:8, John 14:12), Free (John 8:36; Gal. 5:13; 1 Pt 2:16), Holy (1 Pt 1:15–16, 2:9), Pure (Hebrews 9:14, 1 John 3:3, 1 Pt 1:22), Capable (Jn 15:5; 2 Cor 11:5–6), Meaningful (Eph 2:10, Mt 6:30), Sent (Jn 17:18, Matt 28: 18–20; Rm 10:15), Loved (1Jn 3:1; Eph 1:5–6; Gal 2:20)—how might this lower our own defensiveness? How might it make us more accessible, less likely to burn out, less needful to strive, more likely to be a Kingdom resource to those around us? The data suggests that personal and communal spiritual practices focused here could have significant affect.

At the structural level, one thing to consider is how well we are resourcing our spiritual leaders spiritually and emotionally. This data suggests that considering hiring a pastoral position whose sole function is to serve the spiritual and emotional needs of the staff, to engage humility, unresolved shame, and spiritual well-being, to be a “pastor to the pastors” may be warranted. This responsibility often relegates to either the executive or lead pastors’ job description, but the reality is each of those roles have significant other demands that often result in the spiritual development of staff receiving a more minimal focus. From a purely pragmatic perspective, there is potentially significant ROI to be had here. Spending money on a full-time position whose role is to help the other pastoral leaders be fuller expressions of themselves, identifying and working through obstacles like unresolved shame that relate negatively to healthy expressions like humility, should naturally affect the output of all the other roles, increasing creativity, trust, collaboration, and enhancing the effectiveness of the church and academia at all levels.

Another observation invites us to intentionally consider the professional pastoral experience of women. As teachers, conversations and further preparation around the potential issues they may uniquely experience with their professional spiritual well-being appear warranted. Within the church, open dialogue with female staff about how the nature of their role, the culture in which they work, and the external and internal expectations they hold or perceive, may affect their sense of spiritual well-being within their professional life, and should be encouraged.

Similarly, more attention should be paid to the preparation of the first three years of ministry and the final stages of ministry. The data suggests that some form of pairing between older staff and those in their first three years would be helpful for new leaders to process their experience of shame in their role and perhaps would simultaneously help offset the increased professional shame of those who have been Christians for 30+ years. Whether this is tethered to a felt lack of performance, a sense of being underprepared, or comparison to their perception of other leaders, conversations centered on helping young staff making sense out of their learning journey may be beneficial to both groups.

A final and unexpected observation involves the potential value of having both genders represented in decision making. Women reported overall higher perceptions of humility than men, but when specific ministry scenarios were considered, aspects of humility dropped. Men were more likely to acknowledge a sense of God’s presence when having failed others. Women were more likely to perceive and acknowledge the presence of God in positive experiences and acknowledge the experience of others in the midst of personal failings. What this appears to suggest is that mixed gender leadership may have a stronger capacity than single gender leadership to accurately process and make meaning out of the larger picture of a past experience, present moment, or future decision.

The Conclusion

In many ways this research simply reinforces previous assumptions with confirmed data. Pastors are humans: they experience unresolved shame, they need community, their journey of shame has rise and fall, and with this rise and fall their experience of spiritual well-being typically rises and falls as well. However, the data also suggests humility serves as an antidote to this ubiquitous experience of shame. True humility, as O’Brien (1991) notes, moves us to a posture of confidence, increasing our spiritual well-being:

“Humility is not to confused with false modesty or with the kind of abject servility that only repulses…Rather it has to do with a proper estimation of oneself, the stance of the creature before the Creator, utterly dependent and trusting. Here is one well aware both of one’s weaknesses and of one’s glory (we are in His image after all) but makes neither too much nor too little of either.”

As professors and pastors we are invited to embrace our true identity, to lean into the Father and onto one another in humility, to become unencumbered together, freeing us to further offer Christ as the hope to a world whose spiritual well-being has been crushed by the weight of unresolved shame.

References

Dodd, J. & Magnunson, L. (2016), Pastors are People Too. Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook

Miller, J. & Glanz, J. L. (2021). The Personal Experiences of Pastoral Leaders During the COVID-19 Quarantine. Christian Education Journal, 18(3), 500–518.;

Miller, J. & Lemke, D. L. (2022) Hardships, Growth, and Hope: The Experience of Black Pastoral Leaders during a Season of Social Unrest and Covid-19 Quarantine. Journal of Religious Leadership, [s. l.], v. 21, n. 1, p. 51–82, 2022.

Bailey, S. P (2018). In an age of Trump and Stormy Daniels,, evangelical leaders face sex scandals of their own. Washington Post.

Blair, L. (2018). In isolated world of pastors, churches mum on troubling clergy suicides. Christian Post.

Crosskey, L. B., Curry J. F. & Leary, M.R. 2015. Ministry shame and guilt scale. PsycTESTS.

Dwiwardani, C., Hill, P. C., Bollinger, R. A., Marks, L. F., Steele, J.R., Doolion, H. N. & Davis, D. E. (2014). Virtues develop from secure base: Attachment and resilience as predictors of humility, gratitude, and forgiveness. Journal of Psychology & Theology, 42(1), 83-90

Exline, J. J., & Geyer, A. L. (2004). Perceptions of humility: A preliminary study. Self & Identity, 3(2), 95-114.

Gibson, M. (2016). Social worker shame: A scoping review. British Journal of Social

Work, 46(2), 549-565.

Hill, P. C., Laney, E. K., Edwards, K. J., Wang, D. C., Orme, W. H., Chan, A. C., & Wang, F. L. (2017). A few good measures: Colonel Jessup and humility. Handbook of humility, 119-133. In E. L. Worthington, D. E. Davis, & J. N. Hook (Eds.), Handbook of humility: Theory, research, and applications. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Worthington Jr., E. L., & Utsey, S. O. (2013). Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal Of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 353-366.

Keller, K. H., Mollen, D., & Rosen, L. H. (2015). Spiritual maturity as a moderator of the relationship between Christian fundamentalism and shame. Journal of Psychology and Theology, (1), 34.

Kim, S., Thibodeau, R., & Jorgensen, R. S. (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 68-96.

Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

McElroy, S. E., Rice, K. G., Davis, D. E., Hook, J. N., Hill, P. C., Worthington, E. L., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2014). Intellectual humility: scale development and theoretical elaborations in the context of religious leadership. Journal of Psychology & Theology, 42(1), 19-30.

O’Brien, P. T. (1991). The Epistle to the Philippians: a commentary on the Greek text. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Proeschold-Bell, R. J., Yang, C., Toth, M., Rivers, M. C., & Carder, K. (2014). Clergy Spiritual Well-Being Scale. PsycTESTS.

Schaumberg, R. L., & Flynn, F. J. (2012). Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown: the link between guilt proneness and leadership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, (2), 327-342.

Tangney, J. (2000). Humility: Theoretical perspectives, empirical findings and directions for future research. Journal of Clinical and Social Psychology, 19, 70-82.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. (2009). Humility. In The encyclopedia of positive psychology. Lopez, S. ed. Chichester, U.K.; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell Pub., p. 496-502.

_______________

Notes:

[1] A random stratified sample of 1500 pastors of Evangelical and Black Protestant denominations note that 90% (67% strongly agree and 23% somewhat agree) find it important to “work hard to protect their image as a pastor” (Lifeway Research, 2015, p 14).

[2] Unsurprisingly, researchers have had a difficult time identifying a specific percentage of protestant pastors who have had extra-marital affairs. But without sensationalizing a brief google search brings up a variety of leaders names over the past few years.

[3] Research in 2022 identified 42% of respondents articulated a sense of burnout. Pastors Share Top Reasons They’ve Considered Quitting Ministry in the Past Year; Barna Group.

[4] Researcher is happy to provide full results of study and further detail for those of you who, with him, geek out on research data.

[5] This study’s participants scored at a 2.51 average out of 5 for unresolved shame. For context, previous studies on non-Christian undergraduate and graduate students average at 2.81, while minimal previous studies for religious leaders averaged 2.42. For this study at the executive level (n=45) the score was 2.27, while at Associate/Director level (n=95) the score was 2.63.

[6] An average score of 52 on a scale of 13-65, and an average score of 35 on a scale of 9-45.