25 Mar 2021: Dallas Willard on Measuring Matters of the Heart

How do we assess Spiritual Formation in the Age of Accountability?

Dallas Willard originally presented this material to International Forum of Christian Higher Education, March 30, 2006. Here it is reprinted by permission of Dallas Willard Ministries. https://dwillard.org/articles/measuring-matters-of-the-heart

Can we measure, or accurately assess, moral and spiritual development? If so, how? This question is especially apt for those interested in “measuring” such development as a result of the context and training on Christian campuses. Some fairly lavish promises are made by spokespeople for our various schools. How can we be held accountable, by ourselves and others, for the outcomes we promise and hope for? How do we know which outcomes have occurred and why they have occurred?

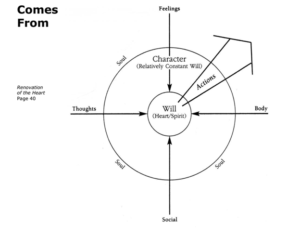

In speaking of “matters of the heart,” we are speaking of character. We are not just interested in actions and declared intentions, or even particular choices. We are, rather, looking at the nature and dynamics of the “hidden” aspects of the self or of the human being as a whole. We are looking at the reliable sources of actions. That is what character means. Consider two diagrams from Renovation of the Heart.

Let us take as a plausible hypothesis that it is possible to know what the character of an individual is, and to know how it may change over a period of time, and why it changed in the way it did. Perhaps this assessment is difficult, and easy to get wrong. But it is fairly obvious in some cases, from reasons that can be given and verified, that some people are self-absorbed, hardhearted, dominated by lust, have no regard for God, or are deceitful, etc. Other people are the moral and spiritual opposites. I suggest that we can assess growth in Christlikeness (the stages or levels of spiritual formation in Christlikeness), and may be able to determine why and how that growth occurs.

Where Action Comes From

We will take Christian “spiritual formation” to be the process through which the individual increasingly comes to resemble Christ in all of the essential dimensions of the self seen in the diagrams. Spiritual formation is not just a matter of increasing willpower or of greater inspiration in the moment of need. To direct the person steadily toward the good, the “heart” (will, human spirit) requires support from every essential dimension of the self. These too must be transformed for character to be established.

Of course Christians constantly evaluate themselves and others as to “spirituality” and moral character. Often because we simply have to—for purposes of placing people in positions of responsibility and evaluating their performance. Or because we enjoy putting people in their place (at least in our own minds) or enjoy gossiping. Or because of our own sense of need to change. Often this is done in uninformed, biased, haphazard and harmful ways. But that is not necessary. It can be done in ways that are intelligent, biblical, helpful, and compassionate.

It should be noted that it is fashionable in some professional circles to disown character evaluations, and to even hold that such evaluations are immoral. Such evaluations are thought to be nonobjective, arrogant, and hurtful to feelings—and feelings are sacred. But this just drives such evaluations underground, for they are unavoidable. We have to make responsible judgments about what people will be likely to do, whether they can be trusted, and how dependable they are—and this cannot be done without assessments of character.

The setting of evaluation is absolutely crucial if it is to be effective, accurate, and helpful; and it must be done in a communal or at least nonindividualistic setting. Here we are specifically talking about the setting of an explicitly Christian community such as a Christian school. For such a setting there will need to be:

- Public statements that substantial growth in Christlikeness is accepted as the norm by the community, and by those who enter the community. Everyone must understand this upon entry or upon considering entry. That this is a communal norm cannot be simply assumed, and the usual data (letters of recommendation, etc.) will not guarantee that people share this understanding. Church membership certainly does not guarantee it.These public statements must not be vague “public relations” talk. The entering student (faculty, staff) must understand that they are accepting the responsibility for their growth in Christlikeness, and that there will be thorough teaching of what this amounts to and fairly precise and realistic expectations that they will grow.

- The expectation and teaching, and the accompanying evaluations, will be done in a spirit of love and acceptance. By taking individuals in, we have made a commitment to them that would mark expulsion as a very extreme measure. It must be understood that evaluation will be without condemnation, attack or withdrawal (distancing), isolation, stigmatization, or gossip. Complete privacy must be an iron rule.

- It is absolutely indispensable that the individual (student, faculty, staff) should own Spiritual Formation, growth in grace, putting on the Character of Christ, as their project. The school is in a helping role only, helping them with the project that they are committed to. It is not the school’s project, in which they must cooperate. It should be understood and explicitly said that procedures of evaluation are for the purpose of aiding the student or others to understand themselves and where they are on the spiritual path with Christ. It is to help them achieve the goals they have committed to as disciples of Jesus and members of your academic community under him. Intelligent and biblical evaluation procedures for spiritual formation simply cannot be done unless the subject desires that it be done. It cannot be done in an adversarial posture. (Here it is useful to rethink the entire matter of “grading.”)

Here schools find a great disadvantage in the fact that “Christians” are not automatically “disciples of Jesus” in any meaningful sense today. What a school teaches and practices on this painful matter will have a direct and substantial bearing on what it can do by way of assessment of character growth. - It should be clear to all that faculty, staff, and administration are all involved in, subject to, the same growth and evaluation process as the students. There will be differences in applications, but it is surely unthinkable that only students should be subject to the norms and evaluation procedures of a spiritual formation program. We cannot follow the saying, “Do as I say, not as I do.” It is also clear that such a program would have to be led from the top level of the school: the Board of Trustees, and the President and his or her staff, must give it central priority. It cannot be left only to designated underlings. The idea that the work of the school is teaching and research in the standardly recognized disciplines, and that all else can be farmed out to Student Life, will require adjustment. Otherwise the common presumption that spiritual growth is not what really matters will continue to prevail and have its effects.

This much, then, on the setting of assessment programs and procedures. It is crucial to say that if needs A-D above are not clearly understood and heartily accepted and communicated by the campus leaders—those who determine policy and practice and preside over its execution—then we should not proceed with serious efforts at assessment of “matters of the heart.” It would be ineffectual and do more harm than good. Of course A-D do not have to be totally worked out before you start some serious assessment. But the clear and clearly understood intent on the part of the school must be there.

What are we testing for? This is something we must be very clear about. And we must be very sure that we are not just testing for conformity to the particular “faith and practice” that distinguishes the school. We will be strongly tempted to do that. So here we will come up against tough theological issues.

- We are not testing for behavior. Behavior/actions must be identified, and in some cases must be dealt with. Behavior creates problems on its own that must be recognized, but actions are symptoms of what we are looking for in assessment of spiritual formation, where we are looking at “the inside of the cup,” to borrow the language of Jesus.

- We are assessing or testing for the sources of behavior in the “hidden” dimensions of the self already referred to.

- The inclusive term for what we are assessing is “love”—love of God and love of neighbor. Here again we take Jesus as our leader, as seen in Mark 12:29-31, drawing together the outcome of the Jewish experience of God. This love is seen through the fruit it produces in character and action, seen in Galatians 5:22-25 and 1 Corinthians 13 and elsewhere. Love is, as the song says, a “many splendored thing,” and we look for it in the many ways it displays itself in the character of individuals. Growth in love is a function of change in the essential dimensions of personality. What is in our mind and feelings, in our body and social relations, as well as in our dispositions of will.Now how do you test for the character of love thus understood? Remember, we are primarily helping the individual subject understand where they are and where they are going.

Certainly actions are indicative of something, and must be noted, but it would never be appropriate to simply draw conclusions from an act that love is or is not the source. Patterns of action over time and in diverse situations are much better indications of character, and tracking these can be illuminative of the state and of changes of the “heart.” The individual can learn much by thoughtful and prayerful interpretations of their

patterns of action.

On the assumption that the evaluation is going to be primarily self-assessment, carefully crafted questionnaires can be used to help the individual recognize the various factors at work and to understand where they are currently, and, possibly, what’s going on in their trajectory through life. Such a questionnaire might be repeated at intervals (say at the end of the semester), possibly revised in ways more aptly suited to show progress or lack thereof in specific dimensions of character. The results should be discussed with the subject in at least one interview, soon after its completion: an interview conducted in the manner of a spiritual director. Perhaps further personal interactions will seem advisable at that point, and could be suggested.

With respect to the questionnaire used, there are several available. The best one available, in my very nonexpert opinion, is The Christian Life Profile, developed in a local church context by Randy Frazee and some of his associates. (Google “Christian Life Profile” to find it.)

Based on the questionnaire and interview, the subject can be directed on how to deal with specific issues: e.g., fear (of various things), anger, cheating, sexual issues, areas where they feel “stuck,” and so forth.

Assessment would have to go hand in hand with teaching. There should be good public teaching on campus that helps students understand why they fail, and what they can do to change the causes of the failures.

Understanding and use of spiritual disciplines is vital for helping people change, and the keeping of a journal on problems and progress will be vital both to teaching and to assessment. It would itself indicate some growth in formation. Intention to grow must be assisted by the willingness to implement means of change in all dimensions of the self, but especially in the thought life. What is constantly before the mind? A journal can be very useful in tracking this and leading to change.

Of course in progression in Christlikeness, the individual increasingly is holistically preoccupied by the good, and not merely with avoidance of evil. This comes through the transformation of each dimension of the self. When the primary pursuit is the good, the true, the beautiful, then evil becomes less and less a thing of interest, less and less before the mind, and temptation therefore is more and more routinely and simply avoided. This can be helpfully tracked by journal keeping, which might then be a subject of discussion with the individual. Just tracking can have an immense effect for spiritual growth, and it lays a foundation for meaningful discussion, or even intervention with means of change.

The combination of (1) observation of patterns of actions, (2) questionnaires with (3) individual guidance/interaction, and (4) journaling can yield the data for reliable assessment of how things are (or are not) changing on the inside of the personal and social life, on campus and off. In particular, these measurements can reveal the degree to which the individual is living the great commandment in every dimension of their personality.

A major issue, now, will be what records are kept, if any, and how they might be used. For example, would a spiritual director write up something (per semester, year, or at completion)? Would it be kept on file or given to the student, or made entirely optional to the student as to what would be done with it? Or would nothing at all be recorded? Or perhaps the subject himself or herself should write up something and decide what should be done with it. Needless to say, these matters have to be handled very carefully, and policies and practices developed tentatively and slowly over the years. They would certainly have to be a part of the explicit understandings of those who enter the community at whatever level.

It would be possible, in a carefully handled program, for the university or college’s selfunderstanding and accountability, to check the substance of their claims to developing character and spiritual growth in their students by keeping records of what is actually happening (according to the above kinds of data) that are totally purged of reference to any individuals or subgroups of individuals. This would serve the school’s need to direct policy wisely and know to what extent their claims about impacting character are true.

“Matters of the heart” can be measured, or at least assessed with substantial accuracy, and, furthermore, we should seriously undertake it. Certainly it can only be done on the basis of a profound understanding and teaching of the spiritual life in Christ.