07 Mar 2022: Attending to Racial Diversity Within ATS: Historical Perspectives, Present Initiatives, and Future Programming

by Mary H. Young (EdD), director of leadership education for the Association of Theological Schools (ATS)

Historical Perspectives

The Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada (ATS) has long advocated for racial/ethnic[1]constituents in its work and continues to attend to their particular experiences of teaching and administering in ATS member schools. Since its original appearance in 1978 as the Committee on Underrepresented Constituencies, the Committee on Race and Ethnicity (CORE), renamed so in 2000, has focused on efforts to encourage inclusiveness in institutional and educational standards. Over the decades, “it has responded to the changing needs of the communities it was intended to serve by expanding its scope and shifting its focus, from curricular change in the 1980s, to the lived experiences of racial/ethnic individuals in theological education in the 1990s, to institutional capacity building in the new millennium.”[2]

The percentage of racial/ethnic faculty and administrators has not kept up with the percentage of racial/ethnic students. The 21st century began with the reality that by mid-century, if not before, persons of color would become the majority in the United States and would be significantly increased in Canada as well. There was a need for the work to focus on issues that prepared both individuals and institutions to do ministry in a society that was rapidly becoming more culturally and ethnically diverse. ATS continues this area of work with the goal that its efforts would affirm racial/ethnic faculty and administrators in their work and increase institutional capacity to support racial/ethnic students and leaders.

In 2015, ATS chronicled 15 years of CORE work in an online Colloquy publication highlighting how the work of CORE has shifted in focus and programming over the years.[3] As the numbers of racial/ethnic persons in theological education increased, CORE’s work shifted from advocacy toward increasing numbers of minorities to nurturing and supporting those minority leaders in their work, a focus that would come to permeate the agendas of all ATS committees and conferences. Critical questions were raised about how best to encourage and retain underrepresented faculty and administrators in theological education, and Lilly Endowment Inc. generously funded seven years of work to support these leaders by examining their unique needs and issues. The programming included racial-specific gatherings, the creation of a diversity folio, and special attention to the inclusion of underrepresented constituents on accrediting visiting teams, boards, and committees.

It soon became clear that while supporting these leaders was absolutely important, it was also necessary to build capacity in their schools in order to sustain the encouragement and affirmation they were receiving through ATS programming. That concern was augmented by a peer review suggesting the rapid changes in North American demographics anticipated by the year 2040. In response, the next seven years of CORE work focused on building institutional skill and capacity related to racial/ethnic faculty and administrators as well as preparing students to minister in diverse contexts. A major aspect of the programming during this reflective shift included a four-year program entitled “Preparing for 2040: Enhancing Capacity to Educate and Minister in a Multiracial World.” In the Preparing for 2040 project, ATS worked with 40 schools that had expressed some desire or commitment to increase their capacity to educate for ministry in a multiracial world. Specifically, participants from these schools sought to work on issues of faculty culture, reframing teaching and learning, understanding race and ethnicity, and conflict resolution.

During this time, ATS saw significant increases in enrollment of racial/ethnic students and employment of racial/ethnic faculty in member schools. Significant revisions were made to the 2010–2012 Standards of Accreditation that would promote diversity and increase access for underrepresented populations.

ATS paused programming in 2014–2015 to evaluate the impact of previous efforts and identify issues for future programming. The year involved four major evaluative activities—both qualitative and quantitative research—involving past participants in CORE programming as well as current students and recent graduates. An extensive discussion of the research process, phases, and findings are available in the ATS journal, Theological Education.[4] Additionally, a summary of the research findings from ATS’s first 14 years of CORE work suggested that individual participation does not guarantee institutional change, institutional capacity does not guarantee individual success, and institutional change needs to be intentional.[5] The varied data gathering processes from this research helped to shape priorities for a grant proposal to fund the focus of the CORE work moving forward.

Present Initiatives and Programming

The current work of the ATS staff and the CORE advisory committee prioritizes the following programmatic areas in response to the research.

- Providing resources for schools such as Engage ATS (an online community for those who work at ATS member schools to network and share resources) as they encounter different institutional tasks related to race, ethnicity, and diversity. The resources will provide the basis for ongoing support of schools.

- Working with an identified group of member schools on educational effectiveness with racial/ethnic students. Teams of faculty and students from participating schools joined other participants in October 2021 to share learnings from a three-year project that will be benefit ATS member schools. Participating schools are currently working with a consultant to deepen their reflections on the strategies they implemented and to develop processes for sustainability. School reports and conversations around their work can be accessed in the Community on Race and Ethnicity at Engage ATS.

- Engaging activities to strengthen collaborative relationships with educational partners such as Hispanic Theological Initiative (HTI), the Forum for Theological Exploration (FTE), Louisville Institute, Hispanic Summer Program (HSP), AETH, In Trust, Wabash Center, and other entities regarding overall systems of support and engagement for racial/ethnic seminary students, PhD students, faculty, administrative staff, and institutions committed to serving racial/ethnic constituencies.

- Implementation of a special initiative for intercultural sensitivity and global awareness training.This initiative is in response to growing interest in and commitment to “race and diversity training” among an increasing number of ATS member schools as part of their institutional and educational practices especially in the context of rapid social, political, and cultural change, including the “browning” of student demographics. We posit that intercultural sensitivity is a central need; and even more so, are the inter-connected needs to (1) have the appropriate tools for the articulation of intercultural sensitivity, (2) the capacity to deploy these tools in learning, teaching, and research, and (3) the development of strategies for ensuring that institutional and educational formation are hospitable and relevant to the education of “browning” student populations.

As the tensions around race and ethnicity have significantly heightened in North America in recent years, ATS has also augmented its ongoing programming on behalf of racial/ethnic constituencies to include the following:

- In June 2020, under the leadership of CORE and the African American presidents and deans, ATS spoke decisively and intentionally into the crisis surrounding the killing of Black people. A Black Lives Matter webinarconvened leading voices from ATS member schools to explore the theological implications of the taking of Black lives and the inherent challenges before the church and the academy. In addition, a Black Lives Matteropen forum invited discussion from ATS executive and academic leaders about the impact and theological work needed to address the consistent killings of Black people.

- ATS continues to partner with racial/ethnic presidents and deans to ensure that their statements of concern around race and justice issues have a platform for distribution among member schools.Those statements, were posted at the ATS website over a period of time, providing opportunities for broad-based education and advocacy.

Reflecting on Racial/Ethnic Data from ATS Schools

A review of ATS institutional data reveals varying observations about enrollment patterns for racial/ethnic students, growth patterns for racial/ethnic faculty and senior administrators, and leadership patterns for women presidents and deans.

Master of Divinity Student Data

A review of racial/ethnic Master of Divinity student enrollment data as compared to white student data reveals significant changes over the last twenty years. To be noted is the increase, across the board, in enrollment of students of color since 2002. Black students represent the largest segment of students of color enrolled at ATS schools with Asian and Visa students following closely behind. The enrollment of Hispanic students has sustained a steady increase from 3% in 2002 to 7% in 2021. The enrollment of Visa students reveals a slightly similar growth pattern though not as rapid, sustaining a 2% increase in student enrollment between 2002 and 2021. ATS began collecting data on “Multiracial” as a category in 2008-2009 and since that time, a significant number of enrolled students have self-identified in that way. As of 2021, 2% of students enrolled in M.Div. programs listed Multiracial as a race category. The chart above shows the decrease in enrollment of White students in M.Div. programs at ATS schools. In 2002, White students represented 72% of the enrolled population and by 2021, that percentage had dropped to 58%. These patterns are a clear indication of the browning of student populations in ATS schools, the implications of which will be mentioned later in this article.

When ATS parses this data out across denominational categories several realties emerge which are not revealed in the composite chart above. Mainline denominations reflect growth in terms of percentages, but not in terms of head count. With the decline in the number of white students the percentage increases for the overall number of racial/ethnic students. When considering evangelical denominations, all racial/ethnic student categories have more than doubled while white student enrollment has only slightly increased. And finally, in the case of Roman Catholic/Orthodox schools there is also growth in all racial/ethnic student categories and significant declines in white students – again translating into relative percentage changes.

Doctor of Ministry Student Data

Enrollment data since 2002 for racial/ethnic D.Min. students at ATS schools reflect a bit of unevenness across a 20 year period. While enrollment of Asian students in D.Min. programs has been up and down, beginning with 14% in 2002 and a slight decrease to 12% in 2021, the growth in enrollment of Black students has been more evident with 10% in 2002 and doubling to 22% in 2021. A similar growth pattern is seen with Hispanic students, though on a much smaller scale. Among Native students, growth has been fairly constant but still remains very small compared to other categories. Finally, over the last 20 years, the enrollment of visa students has gone up from 12% in 2002, peaked at 21% in 2012, and most recently, experienced a decline back to 12% in 2021. As in the case of White student enrollment in Master of Divinity programs, we also see the decrease in D.Min. student enrollment since 2002. In 2002, White students represented 61% of students enrolled in D.Min. programs at ATS schools. In 2021, that percentage had dropped to 46% with students of color representing the majority enrolled in D.Min. programs.

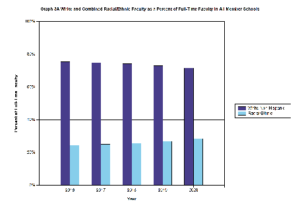

Racial/Ethnic Faculty as compared to White Faculty

Graph 3A below[6] is a five-year view of White and combined racial/ethnic faculty as a percent of full-time[7] faculty in all ATS member schools. Since 2016 the percentage of White faculty in ATS schools has been more than double the percentage of racial/ethnic faculty members combined. To be noted is the slight decline in the percentage of White faculty across the five-year period and the slight increase in the percentage of non-white. When comparing student data with administrator data, one is aware that the percentages of racial/ethnic faculty members at our schools has not kept pace with the rapid browning of student demographics. What does this mean for how students are being formed in their theological studies and the ways in which they are being prepared to serve their varied communities? Are there sufficient enough opportunities available for them to engage mentors and leaders with whom they can relate to culturally who understand the contextual realities of the ministries they serve and lead?

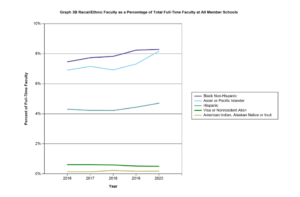

Graph 3B[8] below parses out racial/ethnic faculty as a percentage of total full-time faculty at member schools. There are significantly greater percentages of Black and Asian full-time faculty members in ATS member schools than other racial/ethnic groups. In 2020, each represented a little over 8% of the total number of full-time faculty at ATS schools. While there is about an 8% chasm between the percentages of Black and Asian faculty members and those of Visa and American Indian faculty, the gap closes with Hispanic faculty who in 2020 represent approximately 5% of the total faculty mix at ATS institutions.

Graph 3B[8] below parses out racial/ethnic faculty as a percentage of total full-time faculty at member schools. There are significantly greater percentages of Black and Asian full-time faculty members in ATS member schools than other racial/ethnic groups. In 2020, each represented a little over 8% of the total number of full-time faculty at ATS schools. While there is about an 8% chasm between the percentages of Black and Asian faculty members and those of Visa and American Indian faculty, the gap closes with Hispanic faculty who in 2020 represent approximately 5% of the total faculty mix at ATS institutions.

Racial/Ethnic Senior Administrators as compared to White Senior Administrators

The two charts above provide information on ATS presidents and deans by race/ethnicity from 2017 to 2021. The first chart shows the comparative numbers between the totals for White presidents and deans and those of individual racial/ethnic groups. In this case, the numbers tell the story. The gap is quite apparent with less than 50 racial/ethnic presidents and deans in any given year up through 2021. The second chart provides a close-up view on the five year trajectories across racial/ethnic groups. While some racial/ethnic groups such as the Black and Hispanic leaders have experienced noticeable growth in the numbers of presidents and deans over the five year period, others, like the Asian or Pacific Islander group has maintained a pretty stable and respectable number of senior leaders over the period of time. Visa and Multiracial categories are the lowest and suggest that there is a significant need to search out, mentor, and position those persons for service as senior leaders.

Considering that these racial/ethnic leaders represent a true minority among ATS senior leadership, the Association, through it’s CORE programming, supports racial/ethnic leaders serving as presidents and deans through annual gatherings for peer education and engagement, networking and fellowship opportunities at the Association’s Biennial meetings, and staff resourcing for individual group programming initiatives. These groups, also support each other’s causes, having most recently responded in solidarity to the George Floyd killing and the expanded crisis of the killing of Black and Brown people. ATS works closely with African American, Hispanic, and Asian-descent presidents and deans as they plan annual gatherings, sponsor topic/issue related webinars, and have regular cohort meetings around their work and leadership.

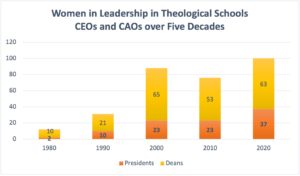

Women Presidents and Deans

Women in Leadership in theological education has been included in the programmatic efforts of The Association of Theological Schools since 1997. The Women in Leadership (WIL) work has been funded across the years by grants from the Carpenter Foundation and the Lilly Endowment. That work has helped to move the needle for the numbers of women in ATS schools serving in senior leadership capacities as presidents and deans over the last 5 decades. In the graph above, data gathered through a women in leadership timeline document, note how the numbers of senior women leaders grew significantly from 1990 with twice the number of women presidents and three times the number of female deans by 2000. Every year since 1990, at least one woman has been named to one of the top two positions at an ATS member school, and there are scores of other women in varied positions whose leadership is critical for thriving institutions. Through my work at ATS, I note that

Women of varied races and ethnicities, varied ecclesial families, varied geographical locations, and varied contextual realities have found sisterhood, mentorship, vocational guidance, and encouragement in their work through the ATS’s Women in Leadership

Program. These gatherings have not only been “holy blessings”, but they have also inspired

a “righteous indignation” about the leadership challenges and inequities that women in

theological education find themselves up against.[9]

A more granular look at specific data related to women of color in senior leadership reveals the following current numbers[10] in the table below. While the number of women CAOs(deans) is much larger than that of the CEOs (presidents), all of these numbers suggest that more work can be done to build pipelines for women in senior leadership positions.

| CEO | CAO | |

| Asian | 1 | 7 |

| Black | 8 | 13 |

| Hispanic | 3 | |

| Native | 1 |

The Association continues its educational support for women administrators and faculty members through annual fall conferences, periodic preconferences for women presidents and deans, and occasional preconference sessions for midcareer women faculty. More recent programming includes a mentoring program and newly developed fall and spring virtual professional development summits.

Concluding Observations and Future Programming

While a significant amount of work has been done and ATS continues to expand its programs and services to member institutions, the racial challenges of today’s society demand even greater attention to matters of race and ethnicity. The Association’s data patterns suggest several observations that are critical for ATS and its future work with members schools around the concerns of race and ethnicity.

The first is the need to pay attention to the rapidly changing student demographics. How might theological schools, through their institutional structures and practices, provide hospitable and equitable learning environments for racial/ethnic students? In what ways do faculty and administrators build capacity around teaching that ensures a justice friendly curriculum and a culturally sensitive learning environment.

A second critical observation is that ATS may need to help institutions equip faculty, staff, and administrators with intercultural awareness and global sensitivity skills as they navigate changing student demographics. Current initiatives through CORE related work are designed to deploy the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) for the purpose of equipping theological school faculty and administrative leaders to become both more interculturally sensitive and competent as part of their vocational, professional, and academic identities.

Finally, the matter of senior leadership for both racial/ethnic administrators and women needs to remain a primary concern for ATS future programming. The numbers of faculty and administrators of color are not changing as rapidly as those of students. How might theological institutions be more intentional with broadening their faculty and staff resources in ways that more clearly reflect the changes in their student bodies? In what ways might ATS programming give attention to and focus on emerging leaders of color whose perspectives, scholarship, and expertise are needed to help shape theological education for a sustainable future? It is hoped that these questions will propel us into practices that equip faculty and administrators and educate students to do ministry in a racially just and culturally diverse world.

[1] “Racial/Ethnic” is a term used in the work of The Association of Theological Schools (ATS) to refer to individuals and communities minoritized by race or ethnicity. The term was first coined by the Association’s Committee on Race and Ethnicity (CORE) more than fifteen years ago as a way to anchor ATS work in diversity and inclusion on race and to avoid mission drift. CORE recently revisited and reaffirmed the use of the term, knowing that it departs from current terminology (e.g., “of color” or “non-dominant”) used in the broader world of higher education and that White is also a race. Members of CORE currently and historically are predominantly racial/ethnic.

[2] Daniel O. Aleshire, Deborah H. C. Gin, and Willie James Jennings, “The Committee on Race and Ethnicity: A Retrospective of 14 years of Work,” Theological Education 50, no. 2 (2017): 21.

[3] For a brief summary of the 15-year review, see Janice Edwards-Armstrong and Eliza Smith Brown, “Committee on Race and Ethnicity completes 15 years of work,” Colloquy Online (January/February 2016). For a more complete overview, see Janice Edwards-Armstrong, “CORE: An Evolving Initiative,” Theological Education 45, no. 1 (2009): 71–76.

[4] The full research report was published in the ATS journal in 2017: Daniel O. Aleshire, Deborah H. C. Gin, and Willie James Jennings, “The Committee on Race and Ethnicity: A Retrospective of 14 years of Work,” Theological Education 50, no. 2 (2017): 21–46.

[5] For a full discussion of these research observations, see Deborah H.C. Gin, “How well are we doing on race? A realistic assessment rooted in research”, Colloquy; Summer, 2018. https://www.ats.edu/files/galleries/how-well-are-we-doing-0001.pdf

[6] ATS Data Tables 2020-2021: 3 – Composition of Faculty and Compensation of Personnel

[7] ATS defines full-time as individuals with faculty status who devote 50% or more of their time to teaching and/or research. ATS Annual Data Tables; Table 1.2 (Glossary) Significant Institutional Characteristics of Each Member School (Glossary), 2020-2021. https://www.ats.edu/files/galleries/2020-2021_Annual_Data_Tables.pdf

[8] Ibid.

[9] Young, Mary H., ed., ATS Women in Leadership: Celebrating Twenty Years (Atla Open Press, 2020), vi.

[10] Source: ATS/COA Database – Women in Leadership 2021 numbers for R/E Presidents and Deans